Author: Kotryna Zukauskaite

Degree: MA Arts and Cultural Enterprise

University: Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

First published as Assessment Evidence for Unit 2 (unredacted): 2017

“The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost.

In its place there is a language of images.

What matters now is who uses that language for what purpose.”

– Berger (1972, p.33)

The purpose of this academic report is to critically evaluate how viewer-initiated digital interaction with art affects the meaning of art beyond the artistic intent and institutional control. The research is based on the case study of an #Artselfie – a phenomena1 of viewer's photographic self-portrait next to the work of art instantly shared on social media networks (such as Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook, and others). In the context described, the paper aims to define the new canon of viewing art through digital engagement with it; analyze observer's experience of art through making an #Artselfie; investigate its effect on the meaning of art beyond original intent by the artist and institutional constraints. This analysis of technology-driven change of experiencing art through reproducing and distributing it is important because it captures the moment of a disruptive shift in the role of a viewer (from passive to active), artist's creative concept (from stable to ephemeral), and institutional boundaries (from authoritative gatekeeper to a democratic forum). The research also leads to a larger – one may even say, political – conversation about media and who controls the meaning of art when it becomes transmittable information (Berger, 1972), as this very issue becomes even more relevant in the digital age, where viewers are enabled to share their experiences with an indefinite number of other social media users. The paper will focus on visual arts and will not investigate the technological participatory factor in other fields, such as theater, music, or literature.

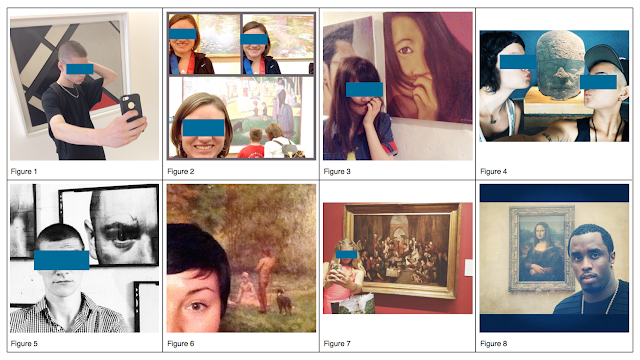

On one hand, extending something with one's presence in the foreground falls into a definition of narcissism2, a continuous representation of oneself through attributes of status, where “art becomes a status-apparatus” (DIS, 2014, p.79). To add to this, “all photographs are memento mori3. To take a photograph is to participate in another person's (or thing's) mortality, vulnerability, mutability” (Sontag, 1972, p.15), though a contrary case can be made, that attaching oneself to a classic work of art (something that survived through ages) is a denial of one's own impermanence (fig.7). Social media only accelerates this constant search for appraisal. Berger's (1972) notion about one becoming a part of the visible world by seeing and being seen, extends to the extreme level of awareness of other people always seeing you simultaneously: “You experience it through other people experiencing your experiences” (DIS, 2014, p.105). Moreover, this continuous construction of non-authentic public self-image through consuming attributes of status (such as art) (fig.8) is also a part of building the personal brand on social media and applying for higher status in the so-called reputation economy: “The #artselfie is driven by who will be seeing it, who will be liking it, its audience score” (2014, p.85). To sum up, taking an #Artselfie is an act of consuming art for reasons of self-representation, where (to turn the classic quote by Marcel Duchamp upside down) the artwork completes the observer.

On the other hand, #Artselfies are not purely self-centric. As previously outlined, they exist only if they circulate, thus it can be argued that personal engagement with art adds to its meaning by distributing it through social media: “Never has an art form captured the act of consumption and the act of production in a single gesture as effectively as the #artselfie” (Jordan in DIS, 2014, p.59). According to Berger (1972, p.24), “in the age of pictorial reproduction the meaning of paintings is no longer attached to them; their meaning becomes transmittable: that is to say it becomes information of a sort”, and as media morphed into social media since, the meaning of art became radically contextualized by being surrounded by a countless number of other imagery, such as family photographs, food selfies, advertising: “The meaning of an image is changed according to what one sees immediately beside it or what comes immediately after it” (1972, p.29). By being reproduced, all art becomes contemporary (Berger, 1972), and so its meaning – relevant, customized, ephemeral, even accidental, and in the case of an #Artselfie – passed on to countless others: “it's value, mediated by so many contingencies, consists in a different system of viewership, one that radically departs from the linear relationship traditionally connecting observer and artwork” (Jordan in DIS, 2014, p.59). Contrary to the criticism of the #Artselfie being a narcissistic act, it can be concluded that this non-linear broadcasting of one's experience of an artwork to an infinite number of changing contexts, is an act of creation of countless new meanings extended from the initial concept of an artwork and even from one's first encounter with it.

Subsequently, the issue of the meaning of art becoming transmittable and highly contextualized information redefines the role of an artist. It can be argued that digital engagement with art extends Becker's (1984) and Bourdieu's (1993) deconstruction of the romantic myth of an artist, a gifted genius producing unique content. If arts meaning becomes physically, individually, and socially readjusted in its #Artselfie-like reproduction, the artist's creative intent becomes only a starting point for infinite amount of fragmented meanings: “The traditional fine arts are elitist: their characteristic form is a single work, produced by an individual; [...] The media are essentially countless” (Sontag, 1977, p.149). Following this logic, Berger's (1972, p.10) definition of artwork as “a record of how X had seen Y” is being extended to how an infinite number of social media users N simultaneously see Z experiencing how X had seen Y. Moreover, Becker's (1984, p.125) thesis formulated as “not knowing who the audience is, artists necessarily make work without knowing who will consume it under what circumstances and with what results” is also being radically updated by an #Artselfie, which potentially enables the living artist to research audience's experiences online and act accordingly, e.g. engage or innovate. A case can be made that this current situation leads to new ways to create: “some art worlds begin with the development of a new audience. The work they produce may not differ much from work in similar genres which preceded it, but they reach a new audience through new distributional arrangements” (1984, p.313). Though it can be argued that not all art was meant to be participatory, all of it still did because of the very existence of an #Artselfie; which causes a substantial shift in the dialogue between an artist and a viewer to a more active one. To sum up, through the act of producing an #Artselfie, the meaning of the artwork breaks the conceptual and compositional boundaries initially outlined by the artist as her creative intent.

Lastly, technological interaction with art entering the mainstream in a shape of an #Artselfie is crucially disruptive to the role of art institutions. Traditionally, preserving, defining, and curating art was based on institutional authority and particular physical space: “The visual arts have always existed within a certain preserve [...] it was the place, the cave, the building, in which, or for which, the work was made. The experience of art [...] was set apart from the rest of life - precisely in order to be able to exercise power over it” (Berger, 1972, p.32). In the Internet era, these physical boundaries are being disintegrated: “what is historically unique in the #artselfie is that it heralds the decentralized, disruptive power of the internet infiltrating the institutionally guarded walls of the art world” (Jordan in DIS, 2014, p.57). Empowered by camera, the viewer is taking control over both – the space, as “[photographs] help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure” (Sontag, 1977, p.9) and arts meaning, as #Artselfie enables the viewer to define, archive, and distribute her experience of art independently from institutional control. On one hand, it may diminish the value of the artwork, preserved and communicated by the institutions, as in photography “no moment is more important than any other moment” (Sontag, 1977, p.28) and so no artwork more important than any other artwork. On the other hand, “#artselfie can be read as a commentary about the way people do not enjoy art individually but as a mass” (Castets in DIS, 2014, p.105), which is a radical turn to the democratization of experiencing art, breaking away from the controlled environment. In the Internet era, the experience of art doesn't end inside the institution, the meaning of art leaves the physical space and enters the digitally social one, carrying out “a promise inherent in photography from its very beginning: to democratize all experiences by translating them into images” (Sontag, 1977, p.7). In summary, producing an #Artselfie is viewer's way of taking control of the space around the artwork and extending the meaning of art beyond the institutional guard, which is a process of art's democratization, a fundamental shift from being overpowered by art's imposed uniqueness to putting human experience – individual and social – first.

In conclusion, technology-driven #Artselfie enables to engage with art rather than passively observe it; transforms the meaning of art into an infinite number of fragmented meanings; breaks the compositional and conceptual boundaries initially outlined by the artist; democratizes the experience of art by expanding it beyond institutional constraints. These disruptions put the viewer into a larger context of “including yourself in the dissemination of a [art]work and participating in the history of art” (DIS, 2014, p.89), predicted by Berger (1972, p.33) long before the digital era: “If the new language of images were used differently, it would, through its use, confer a new kind of power. Within it we could begin to define our experiences [...] Not only personal experience, but also the essential historical experience of our relation to the past: that is to say the experience of seeking to give meaning to our lives, of trying to understand the history of which we can become the active agents”. One may argue that this quote defines image-sharing platforms where archived personal encounters with art sum up to a larger historical feed bridging the gap between the art and the rest of life; past and presence. This technological empowerment of the observer potentially leads to new possibilities of embracing the mainstream viewer beyond just tolerating or even regulating4 her preferred ways to experience; innovative methods of direct communication between the artist and the audience; unconventional forms of archiving viewer's experiences and ways of including them in the official version of the art history, still documented largely by art institutions. Are everyone's experiences equal? Should some art still be guarded against uninvited participants? Will the awareness of #Artselfie's existence somehow change the policy, curatorial decisions, or even the physical space of art institutions in the long perspective, beyond the recent trend? Will there be any curatorial backlash to photogenic art, however positively affecting attendance numbers? How do #Artselfie-like reproductions affect art's value – both symbolic and monetary? These questions sum up to a much larger one: to whom does the meaning of art belong (Berger, 1972)? To its initial creators, preservers, or those experiencing art and applying it to their own lives?

1#Artselfie – a social media hashtag “launched and promoted shortly before Art Basel Miami Beach through [DIS Collective's] online platform, DIS Magazine” (DIS, 2014, p.57). It became a global phenomena after Beyonce's & Jay-Z's tour to the Louvre and Frieze London, where they posed with classic and contemporary artworks, “pushing the #artselfie to new heights” (Cascone, 2014). DIS still keeps archiving all Instagram entrances hashtagged with #Artselfie at Artselfie.com.

2Narcissism – “1. Excessive interest in or admiration of oneself and one's physical appearance. [...] 1.2 Self-centredness arising from failure to distinguish the self from external objects [...]” (Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2017).

3Memento mori – “An object kept as a reminder of the inevitability of death” (Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2017).

4E.g. announcing Museum Selfie Day / Weekend only on particular dates.

Reference List:

Becker, H. (1984). Art worlds. Reprint 2008. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. Reprint 2008. London: Penguin.

Bourdieu, P., 1993. But who created the creators. Sociology in question, pp.139-148.

DIS (2014). #artselfie. 1st ed. Paris: Jean Boite Editions.

Referred to in footnotes:

Cascone, S. (2014). Beyoncé and Jay Z Take Frieze, Pose with Mona Lisa. [online] artnet News. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/beyonce-and-jay-z-pose-with-mona-lisa-135748 [Accessed 5 May 2017].

DIS (2017). #ArtSelfie [online] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 21 May 2017].

Oxford Dictionaries | English. (2017). Oxford Dictionaries - Dictionary, Thesaurus, & Grammar. [online] Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/ [Accessed 4 May 2017].

Bibliography:

Benjamin, W. and Underwood, J. (2008). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. 1st ed. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Bourdieu, P. and Johnson, R. (1993). The field of cultural production. Reprint 2016. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Busetta, L. and Coladonato, V., 2015. Introduction Be Your Selfie: Identity, Aesthetics and Power in Digital Self-Representation. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 8(6).

Charney, N. (2017). This is your brain on selfies: The science of self-portraits, faces, art and the mind. [online] Salon. Available at: http://www.salon.com/2017/01/08/this-is-your-brain-on-selfies-the-science-of-self-portraits-faces-art-and-the-mind/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Colberg, J. (2012). Meditations on Photographs: A Car on Fire at the Mall. [online] Jmcolberg.com. Available at: http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/extended/archives/meditations_on_photographs_a_car_on_fire_at_the_mall_by_jmc/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Di Foggia, G., 2015. About the Anti-Figurativeness of# selfie.(Location of# selfie). Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 8(6).

Düttmann, A. (n.d.). Is there a Self in Selfies?. [online] IIIIXIII. Available at: http://www.fourbythreemagazine.com/issue/imagination/is-there-a-self-in-selfies-alex-duttmann [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Evans McClure, S. (n.d.). The Mythical Millennial in Museums. [online] MuseumNext. Available at: https://www.museumnext.com/insight/the-mythical-millennial-in-museums/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Gopnik, A. (2015). Finding the Self in a Selfie. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/finding-the-self-in-a-selfie [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Guenther, A. (2014). Today ’s Curation: News of the Art Museum and the Crowd. 1st ed. [ebook] Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=journalismprojects [Accessed 21 Apr. 2017].

Jones, J. (2012). Join Instagram, join a collective act of self-delusion | Jonathan Jones. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/19/instagram-collective-act-self-delusion [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Hirstein, W. and Campbell, M. (2009). Aesthetics and the Experience of Beauty. In: Encyclopedia of Consciousness, 1st ed. Oxford: Elsevier, pp.1-7.

Housen, A., 2007. Art viewing and aesthetic development: Designing for the viewer. From periphery to center: Art museum education in the 21st century, pp.172-179.

Horning, R. (2014). Selfies without the self. [online] The New Inquiry. Available at: https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/selfies-without-the-self/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Howorus-Czajka, M. (2015). Incorporating the Viewer into the Picture/Incorporating the Picture into New Media in the Art of Dominik Lejman. In: Provocation as Art, Scandal, Shock and Sexuality in Contemporary Visual Culture. [online] pp.64-75. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/22056369/Incorporating_the_Viewer_into_the_Picture_Incorporating_the_Picture_into_New_Media_-_the_art_of_Dominik_Lejman [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Kandel, E. (2013). Opinion | What the Brain Can Tell Us About Art. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/14/opinion/sunday/what-the-brain-can-tell-us-about-art.html [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Kandel, E. (2016). Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures. 1st ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kandel, E. (2016). What is art for? Science shows it’s in the eye—and brain—of the beholder. [online] Theartnewspaper.com. Available at: http://theartnewspaper.com/comment/what-is-art-for-science-shows-it-s-in-the-eye-and-brain-of-the-beholder/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Kandel, E. (2016). What is Art for?. [video] Available at: http://theartnewspaper.com/multimedia/video/61/204280/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Marchese, S. and Marchese, F. (1995). Digital Media and Ephemeralness: Art, Artist, and Viewer. Leonardo, 28(5), p.433.

Midgette, A. (2013). On the Prowl for Memories, Museum Goers Resort to Snapshots. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/on-the-prowl-for-memories-museumgoers-resort-to-snapshots/2013/10/03/051d5924-2790-11e3-b3e9-d97fb087acd6_story.html?utm_term=.0ce1593abfc1 [Accessed 23 Apr. 2013].

Midgette, A., Viswanathan, V. and Moynihan, S. (2013). Making Most of Your Museum Visit. [video] Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/on-the-prowl-for-memories-museumgoers-resort-to-snapshots/2013/10/03/051d5924-2790-11e3-b3e9-d97fb087acd6_story.html?utm_term=.352adceeaddf [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Miranda, C. (2013). Why Can’t We Take Pictures in Art Museums?. [online] Artnews.com. Available at: http://www.artnews.com/2013/05/13/photography-in-art-museums/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Morley, C. (2013). Viewer As Author: The Impact of Participatory Artwork upon Twenty-First Century Art Discourse. Master of Arts. The University of Manchester.

Muñoz-Alonso, L. (2014). Beyoncé and Jay Z Start the Art Selfie Movement. [online] artnet News. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/beyonce-and-jay-z-elevate-the-art-selfie-into-a-movement-147046 [Accessed 5 May 2017].

Oelze, S. (2015). The ego as a work of art: From self-portraits to selfies. [online] DW.COM. Available at: http://www.dw.com/en/the-ego-as-a-work-of-art-from-self-portraits-to-selfies/a-18843991 [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Rinaldi, R. (2012). Art and the active audience: Participatory art changes audience role from viewer to doer. [online] Denverpost.com. Available at: http://www.denverpost.com/2012/12/31/art-and-the-active-audience-participatory-art-changes-audience-role-from-viewer-to-doer/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

de Seta, G. and Proksell, M., 2015. The Aesthetics of Zipai: From Wechat Selfies to Self-Representation in Contemporary Chinese Art and Photography. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 8(6).

Yue, M. (2017). Why Museums Need to Embrace Duck Lips and Other Poses. [online] Mascola.com. Available at: http://mascola.com/insights/user-generated-content-for-museums/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Williams, Z. (2014). Selfie-portrait of the artist: National Gallery surrenders to the internet. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/15/selfie-portrait-artist-national-gallery-surrenders-to-internet [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Ziegler, M. (2016). How To Find Your True Self In A Selfie Obsessed World. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/maseenaziegler/2016/07/21/how-to-find-your-true-self-in-a-selfie-society/#34756880178e [Accessed 23 Apr. 2017].

Illustrations:

Figure 1: @mattardell (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 2: @jedijen11 (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 3: @aggiezane (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 4: @christelle_nyc (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 5: @mathieucenac (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 6: @certified_angle (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 7: @emerexplainsitall (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://artselfie.com/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

Figure 8: @diddy (n.d.). #Artselfie. [image] Available at: http://thechive.com/2011/12/23/rappers-doing-normal-sht-30-photos/ [Accessed 24 May 2017].

-->