Author: Kotryna Zukauskaite

Degree: MA Arts and Cultural Enterprise

University: Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

First published as Assessment Evidence for Unit 3 (unredacted): 2017

Toxic Art by John Sabraw

The

purpose of this report is to analyze John

Sabraw's project Toxic

Art

as an example of a successful

attempt to engage with the global environmental challenge of

industrial water pollution on a local scale through artistic

practice, interdisciplinary research, and entrepreneurial strategy.

Therefore, the

paper investigates the initiative in a context of sustainable

development as environmentalism and “its interconnection to the

social and economic dimensions” (Anheier

and Isar, 2010, p.206). Moreover, as Toxic

Art

falls

within the category of

a self-sustaining cycle that recycles something dangerous (toxic

sludge) into something useful (artist's paints) to create something

meaningful (art), this report argues its success as an Ecovention—“an

artist-initiated project that employs an inventive strategy to

physically transform a local ecology” (Spaid, 2012, p.1). To do so,

the paper outlines the initiative, explores its success as a

self-sustaining business model, explores the interdisciplinary

collaboration between art and science, and, in this context,

discusses the shifting position of the eco-conscious artist who

oversteps the traditional boundaries of the art world. This analysis

is important because it demonstrates how an inter-disciplinary

approach can empower the cultural sector in its engagement with a

global issue on a local

scale.

Toxic

Art

is an Ecovention

initiated by John Sabraw, environmentalist and Professor of Art at

Ohio University, alongside Guy Riefle, Associate Professor of Civil

Engineering. The initiative focuses on cleaning and reviving

biologically dead rivers

in the State of Ohio that have been polluted by abandoned coal mines:

“operators of the mines simply picked up and left, since, prior to

the act1,

they had no legal obligation to restore the land to its previous

condition” (Gambino, 2013, n.p.). After the mines' closing, a

network of underground passages had been flooded, and as oxygen in

the water reacted with minerals in the rock, picking up high iron and

aluminum levels, the water's pH decreased and, when streamed to the

local watershed, extinguished all aquatic life in the area (2013).

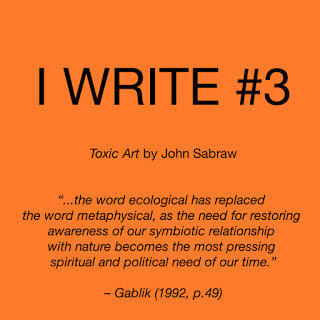

The team of artists and scientists developed a method of extracting

iron oxidants from the river and recycling them into rich pigments

(fig.1), perfect for producing acrylic or oil-based paint (Sabraw,

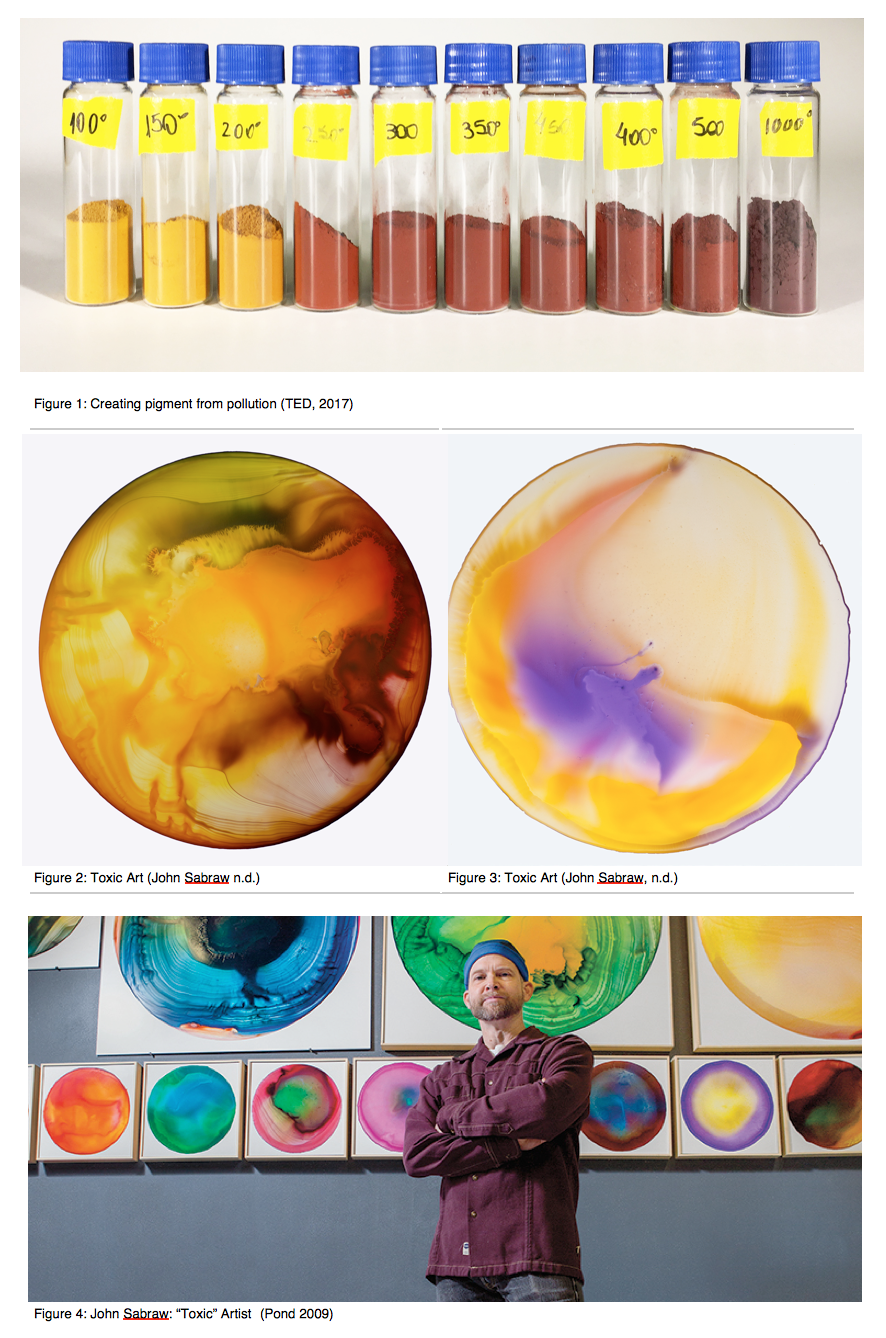

n.d.). Beyond the highly publicized Toxic

Art

exhibition2

of Sabraw's abstract art made with this paint (fig.2,3,4), the

pigment production process showed some potential for commercial

development3,

which hinted at a possible source of income to keep the environmental

effort going. To summarize, the project focuses on a defined area and

aims to recycle pollutants into a commercially valuable product, and,

in this way, to fund the environmental cause and create art in the

process.

Approaching

sustainability objectives from an entrepreneurial angle enabled the

project to develop a financial strategy to effect lasting change.

There are three streams of funding planned for the effort. The first

is commercial profit from a collaboration with Gamblin

Artists Colors, who are in the process of producing the first batch

of pollutant-based paints and putting them on the market in 20184,

according to Sabraw (2017). The second flow of income comes from

sustainable art sales: “some of the paint would be given at no cost

to artists who are creating sustainable artwork, and profits from the

portion that's sold

will go towards the cleanup” (Sabraw in Alaimo, 2017). The third is

government funding: “we have just received funding for two years to

build and operate a scaled pilot [water treatment]

plant

in Corning, Ohio. This will be the culmination of all our efforts. We

will be able to prove the efficacy of our process

on site <...> Once we have proved this - we can lobby

government entities to build a full-scale plant and clean up these

toxic seeps” (Sabraw, 2017).

However, the team is being very realistic about their profit goals:

“even if we just break even, that would be a success, because we

would be cleaning up a devastated stream for free and creating a few

local jobs” (Sabraw in Gambino, 2013). In summary,

the entrepreneurial logic and financial planning behind the activism

aim to see the reclamation pay for itself and fund the team's

long-term commitment to sustainable production patterns5.

Moreover,

the project is defined and enriched by interdisciplinary

collaboration between art and science. First of all, integrating

different competencies to achieve a common goal is critically

important because, as formulated by Gablik, “Western culture has

been pervasively shaped by this assumption of separateness as the

absolute foundation on which we live our lives. Today with the future

of the planet in doubt <...> we need integral awareness in

every field” (1992, p.50). Secondly, scientific research provides

technological tools and techniques that artists wouldn't be able to

access otherwise (e.g. laboratory equipment, methodologies of

monitoring the process and its results). Thirdly, art provides a

social perspective on scientific research by communicating a complex

technological concept on a human level, attracts media attention, and

engages a broader audience: “when it comes to art, sponsors don't

weigh practical priorities or expect to make a profit, the way

funders of scientific research do. Art is viewed as a positive

contribution that makes a long-term restoration project immediately

attractive to a wider audience” (Spaid, 2012, p.1). By and large,

an interdisciplinary approach to environmental art extends its scope,

provides tools for measuring results, and raises public

awareness of a complex scientific issue.

In

conclusion, the success of Toxic

Art

as a self-funded cycle of sustainable production is based on a

consolidation of artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial approaches

to environmentalism. The case study is defined by an eco-conscious

artist overstepping traditional boundaries of the art world to become

a part of something bigger than his self-expression. As Gablik (1992,

p.49) describes, “the word ecological

has replaced the word metaphysical,

as the need for restoring awareness of our symbiotic relationship

with nature becomes the most pressing spiritual and political need of

our time.” Moreover, the project's interdisciplinary spirit

directly proves H.S.Becker's classic notion, that “art worlds do

not have boundaries around them so that we can say that these people

belong to a particular art world while those people do not” (1984,

p.35). This open attitude toward change also shifts the position of

the artist in and beyond the art world, and opens new paths for

further action: “I've gotten a tremendous response to my work from

around the world <...> What is my responsibility now? How can I

have a greater impact?” (Sabraw in Alaimo, 2017). Arguably, this

global response to a local achievement is both evidence of success

and a burden of responsibility to spread the local model on a global

scale.

1Refers

to the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977.

2As

opposed to the nature of most Ecoventions

that end as public

works (e.g. sewage and waste-water treatment plants), contributing

to their invisibility (Spaid 2012), the Toxic

Art

project was highly publicized by mainstream media (e.g. The

Washington Post,

BBC, Huffington

Post)

and more specialized publications (e.g. Smithsonian,

New Scientist, Scientific American).

3“To

make paints of these colors, international companies basically mimic

this reaction, adding chemicals to water tanks containing scrap

metals” (Gambino 2013)

4It

is important to note that, by becoming an enterprise, the group of

activists accepted their responsibilities by “being mindful to

create something that is economically viable and that meets industry

standards” (Gambino, 2013).

-->

5Which

also fits a definition of one of the Sustainable Development Goals

outlined by United Nations as, “to ensure sustainable consumption

and production patterns” (United Nations, 2017).

REFERENCE

LIST:

Anheier,

H. and Isar, Y. (2010). Cultures and Globalization: Cultural

Expression, Creativity and Innovation. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Alaimo,

C. (2017). Gallery: Pretty poison. [online]

ideas.ted.com. Available at:

http://ideas.ted.com/gallery-pretty-poison/ [Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Becker,

H.S. (1984). Art worlds. Reprint 2008. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Gablik,

S., 1992. The ecological imperative. Art Journal, 51(2),

pp.49-51.

Gambino,

M. (2013). Toxic Runoff Yellow and Other Paint Colors Sourced

From Polluted Streams. [online] Smithsonian. Available at:

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/toxic-runoff-yellow-and-other-paint-colors-sourced-from-polluted-streams-17561886/

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Sabraw,

J. (2017). A question from MA student, CSM (UAL).

Interviewed by Kotryna Zukauskaite. [e-mail]. 11 July, 2017.

Sabraw,

J. (n.d.). John

Sabraw.

[online] John Sabraw. Available at: http://www.johnsabraw.com/

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Spaid,

S. (2002). Ecovention: Current art to transform ecologies .

Cincinnati: Contemporary Arts Center. Available at:

/www.Greenmuseum.org. [Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

ADDITIONALLY

REFERRED IN FOOTNOTES:

United

Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Sustainable

development goals - United Nations. [online] Available at:

http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

[Accessed 23 Jul. 2017].

ILLUSTRATIONS:

Figure

1: TED

(2017). Creating

pigment from pollution.

[image] Available at:

https://tedideas.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/web_ready_toasted-line-of-test-tubes-2-1.jpg?w=2000&h=806

[Accessed 24 Jul. 2017].

Figure

2: Sabraw, J. (n.d.). Toxic

Art.

[image] Available at:

https://tedideas.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/we_ready_chroma-s1-17-36x36-inches-1.jpg?w=2000&h=2004

[Accessed 24 Jul. 2017].

Figure

3: Sabraw, J. (n.d.). Toxic

Art.

[image] Available at:

https://tedideas.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/web_readyebb132134.jpg?w=1800&h=1797

[Accessed 24 Jul. 2017].

Figure

4: Pond, L. (2009). John

Sabraw: “Toxic” Artist.

[image] Available at:

http://www.northwestern.edu/magazine/summer2014/images/large-images/CU_%20John%20Sabrawr1_L.jpg

[Accessed 24 Jul. 2017].

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Art

the Science Blog. (2016). CREATORS

– John Sabraw.

[online] Available at:

https://artthescience.com/blog/2016/07/04/creators-john-sabraw/

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Brooks,

K. (2013). Artist Paints With Toxic Sludge In An Effort To

Raise Awareness Of Coal Mining Pollution. [online] HuffPost.

Available at:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/28/john-sabrow_n_3824917.html

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Dauray,

M. (n.d.). John Sabraw: Eco-Conscious Artist and Alchemist.

[online] Healing-power-of-art.org. Available at:

https://www.healing-power-of-art.org/john-sabraw-eco-conscious-artist-and-alchemist/

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Dean,

D. (2013). Artist John Sabraw. [online] Serial Optimist.

Available at:

http://www.serialoptimist.com/interviews/artist-john-sabraw-13791.html

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Fazeli

Fard, M. (2013). Pollution transformed from health concern to

art piece. [online] Washington Post. Available at:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/pollution-transformed-from-health-concern-to-art-piece/2013/09/09/c9cbd55c-10c5-11e3-bdf6-e4fc677d94a1_story.html?utm_term=.dd7520ff5910

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Gamblin

Artists Colors. (n.d.). Gamblin Artists Colors. [online]

Available at: https://www.gamblincolors.com/ [Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Gibson,

A. (2012). OHIO: Research |Earth Works: Artist John Sabraw

makes a case for sustainable art in a new series of paintings that

celebrate the natural world. [online] Ohio.edu. Available at:

https://www.ohio.edu/research/communications/earthworks.cfm [Accessed

18 Jul. 2017].

Kagan,

S. (2011). Art and Sustainability: Connecting Patterns for a Culture

of Complexity, Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld. Available from: ProQuest

Ebook Central. [18 July 2017].

Minerals.ohiodnr.gov.

(n.d.). AML

Reclamation Programs.

[online] Available at:

http://minerals.ohiodnr.gov/abandoned-mine-land-reclamation/aml-reclamation-programs

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Pope,

L. (2013). Toxic sludge from polluted rivers turned into art.

[online] New Scientist. Available at:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21929300-100-toxic-sludge-from-polluted-rivers-turned-into-art/

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Suplinskas,

G., 2016. Realizing Urban Water Pollution Impact In Melbourne,

Australia Through Painting.

Ohio.edu.

(n.d.). John Sabraw. [online] Available at:

https://www.ohio.edu/finearts/art/faculty-staff/profiles.cfm?profile=AD8190E9-5056-A800-488512189491E533

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

Ohio.edu.

(n.d.). R. Guy Riefler. [online] Available at:

https://www.ohio.edu/engineering/about/profiles.cfm?profile=61584988-5056-A800-48E43A5B68E10135

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

What

is Acid Mine Drainage. (n.d.). [pdf] U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA). Available at:

http://www.sosbluewaters.org/epa-what-is-acid-mine-drainage%5B1%5D.pdf

[Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].

MULTIMEDIA:

Koestler,

J. (2017). Toxic Art. [video] Available at:

http://www.johnsabraw.com/video/ [Accessed 13 Jul. 2017].

-->

Toxic

art | John Sabraw | TEDxWarwick. (2017). [video] Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Qz1HVcRu7g [Accessed 18 Jul. 2017].